Python's Zen is where most of the Software Design and Development terms are explained pretty simply in. It's created by Tim Peters and all it takes to print out the full list of Zen is to run the following command in your terminal.

$ python -c 'import this'

When importing this module, it prints out a list of meaningful metaphors. Here would be the result of that command.

The Zen of Python, by Tim Peters

Beautiful is better than ugly.

Explicit is better than implicit.

Simple is better than complex.

Complex is better than complicated.

Flat is better than nested.

Sparse is better than dense.

Readability counts.

Special cases aren't special enough to break the rules.

Although practicality beats purity.

Errors should never pass silently.

Unless explicitly silenced.

In the face of ambiguity, refuse the temptation to guess.

There should be one-- and preferably only one --obvious way to do it.

Although that way may not be obvious at first unless you're Dutch.

Now is better than never.

Although never is often better than *right* now.

If the implementation is hard to explain, it's a bad idea.

If the implementation is easy to explain, it may be a good idea.

Namespaces are one honking great idea -- let's do more of those!

Today, we're going to dive a little deeper into the meaning of some items from the Zen list and simplify them via examples in Python just in case we find a better understanding of them. We're not going to cover every and each item but you'll find out more about the art of Software Design as you follow along.

"Beautiful is better than ugly"

Well, of course, a piece of code could be either awesome-looking or ugly as hell. The term "Beautiful" does not do anything with the output of your program. All we're discussing throughout this article is about reviewing and how your code should look to another. Check the following examples.

# Ugly 🤢

def a(n):

if not n:

return f'Hello World'

return f'Hello {n}'

Whereas an experienced (smart) Python developer would use a proper naming convention and type annotations for better self-explanatory code.

# Beautiful 😍

def greet(name: str = 'World') -> str:

"""

greets the entered name repectfully.

Args:

name: someone's name. Defaults to "World".

Returns:

"Hello {name}" and if `name` is none, "World" will

be replaced with `name`.

"""

return f'Hello {name}'

Note: You may not need such a long detailed docstring for a small function that all it does is quite obvious by looking over its name.

"Simple is better than complex"

Sometimes, writing simple codes requires the wisdom of the developer. Writing simple codes is harder than writing complex ones. Having a deep knowledge of Python helps you act pretty smart. Using complex statements and solutions does nothing but slow down your development process and the whole team.

# Complex 🤢

def add_enumeration(names: list) -> dict:

full_names = {}

counter = 1

for item in names:

full_names[counter] = item

counter += 1

return full_names

names = ['Jane', 'Jack', 'John']

names = add_enumeration(names)

Well, you could've easily used enumerate in Python for this case. No need for a new function declaration then.

# Simple 😍

names = ['Jane', 'Jack', 'John']

names = dict(enumerate(names, start=1))

As long as you have to move your eyes back and forth over a function body in order to understand what it actually does, it's counted as a complex function, and you have to consider taking some time to refactor it. I call this moment a "WTF.. Aha.." moment.

"Sparse is better than dense"

Using multiple inner if-else statements and for-loops would cause your code to become a little bit hard to review. That's fine using comprehensions but be careful. Using list comprehensions should not make you feel like a pro!

# Complex 🤢

graph_info = [{i: [round(j), round(i)]} for i, j in zip(z_inx, x_inx)]

Instead, I would recommend defining a function out of this complicated nested list comprehension.

# Simple 😍

def get_graph_info(z_inx: list, x_inx: list) -> list:

info = []

for i, j in zip(z_inx, x_inx):

info.append({

i: [round(j), round(i)]

})

return info

Using safe simpler comprehension is always recommended specifically within the body of the small functions.

"Readability counts"

Code readability is an essential aspect of writing maintainable and efficient code. It refers to how easy it is for others (and yourself) to understand and follow the logic of your code.

To keep your code more readable, consider reviewing your codes over and over. Once you're done coding, it's time for refactoring and cleaning to make sure you've used proper conventions. For instance, instead of using x and y, you've used width and height and so on.

Using comments is fine but don't waste your time writing too much of them. You're not supposed to maintain useless comments but the actual working codebase. Write comments when you think your code is already clean and self-explaining but needs to be more descriptive and obvious.

"Errors should never pass silently"

At this point, we're talking about runtime-type errors and exceptions. Well, it must be quite obvious that you have to catch the exceptions in the proper ways and be careful of the scope within try because anything might happen there.

# Don't 🤢

def divide_numbers(x: float, y: float) -> float:

try:

result = x / y

except:

print('An error occurred!')

return result

At this point, we're dealing with all exception types in the same way. Even if the user's inputs were correct if we make a SyntaxError within the try scope, the except scope would catch it.

# Do 😍

def divide_numbers(x: float, y: float) -> float:

try:

result = x / y

except ZeroDivisionError:

print('Oops! You can\'t divide by zero.')

except TypeError:

print('Invalid input. Please enter numbers only.')

return result

It's always recommended to log the raised exception as well.

# Tip 💡

try:

...

except Exception1 as e:

logging.log(f"Exception raised {repr(e)}")

...

except Exception2 as e:

logging.log(f"Exception raised {repr(e)}")

...

"Now is better than never"

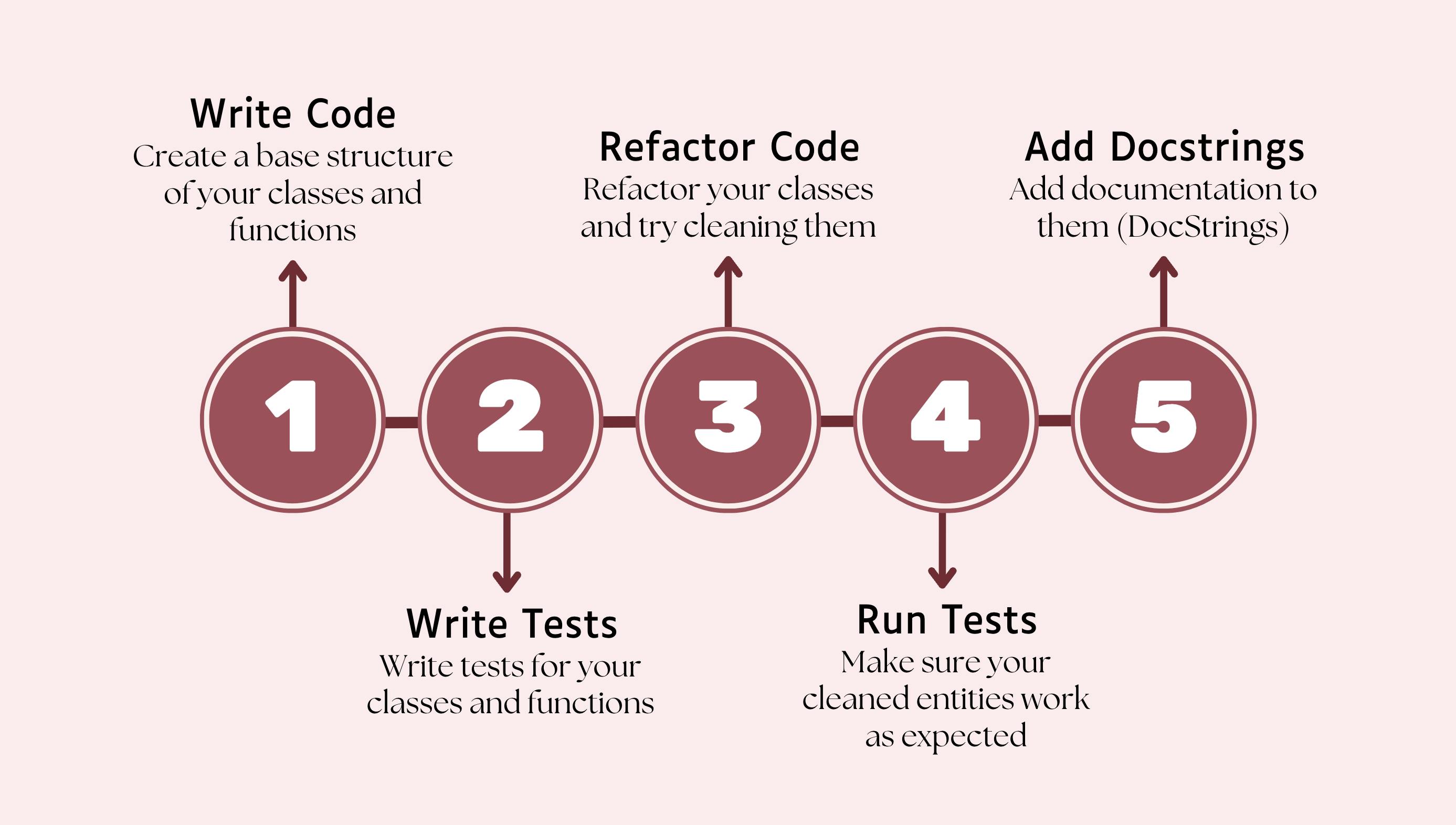

Always keep the following development cycle in your mind. It makes your code more maintainable and causes a good Development Experience (DX).

Conclusion

In this part, we reviewed some items from Python's Zen list and discovered them with various examples. Hope they've given you a proper perspective about software development.